|

Sellers, leaders, trainers, and service professionals, therefore, should not just be focused on the solution (the outcome); they should be focused on how the process toward that outcome is experienced. The process – or experience – is “delightful” when the user (or customer or trainee) returns consciously or subconsciously to the process. They know the thing that pleased them and are there to seek it again. Or they don’t know exactly what it was, but they remember how they felt and are happy to return to the entire experience. To put it simply, then: build toward the total experience. To put it even more simply: build the total experience.

0 Comments

Our webinar for Teachers College alumni is now available on YouTube.

Here is a quick whiteboard that was used as an example of active listening while Steve was talking about 'delight' during an online webinar.

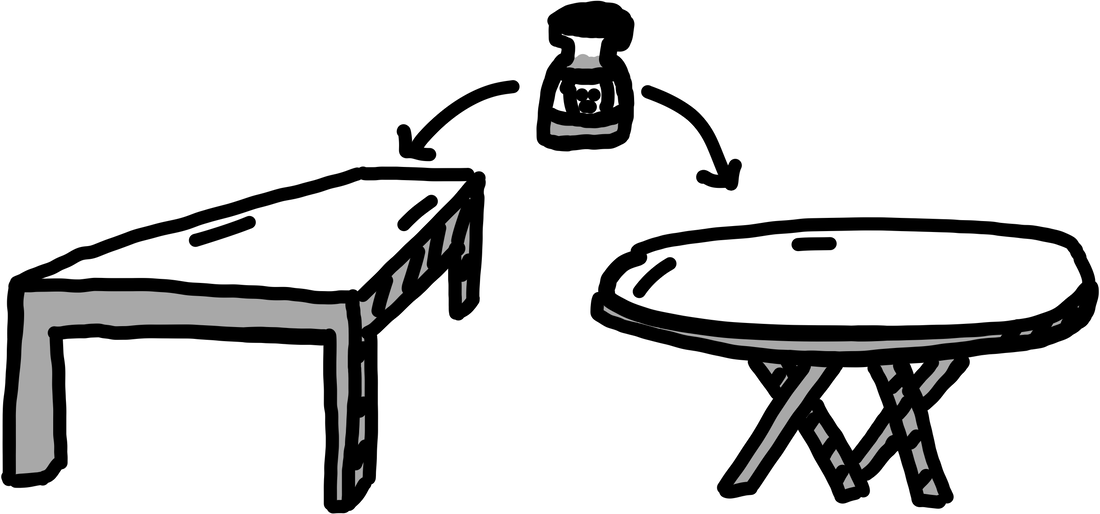

And regardless, this was more than a sales transaction. It was also a teaching environment. The business development executive knew that, even if he didnt’ articulate it to himself or to the customers. He had acquired information about two people who were trying to understand, so as to act, and he was using that information the way a good teacher would — when it could shift understanding and behavior in a manner that actually improved an outcome for a learner. Because, in the case of dining room tables, the customers were nothing if not learners — two people processing information as quickly as possible and trying to use it to take the next step in a project or task.

The educational driver of immediacy is feedback, and we have more to wring from it before turning our attention elsewhere.

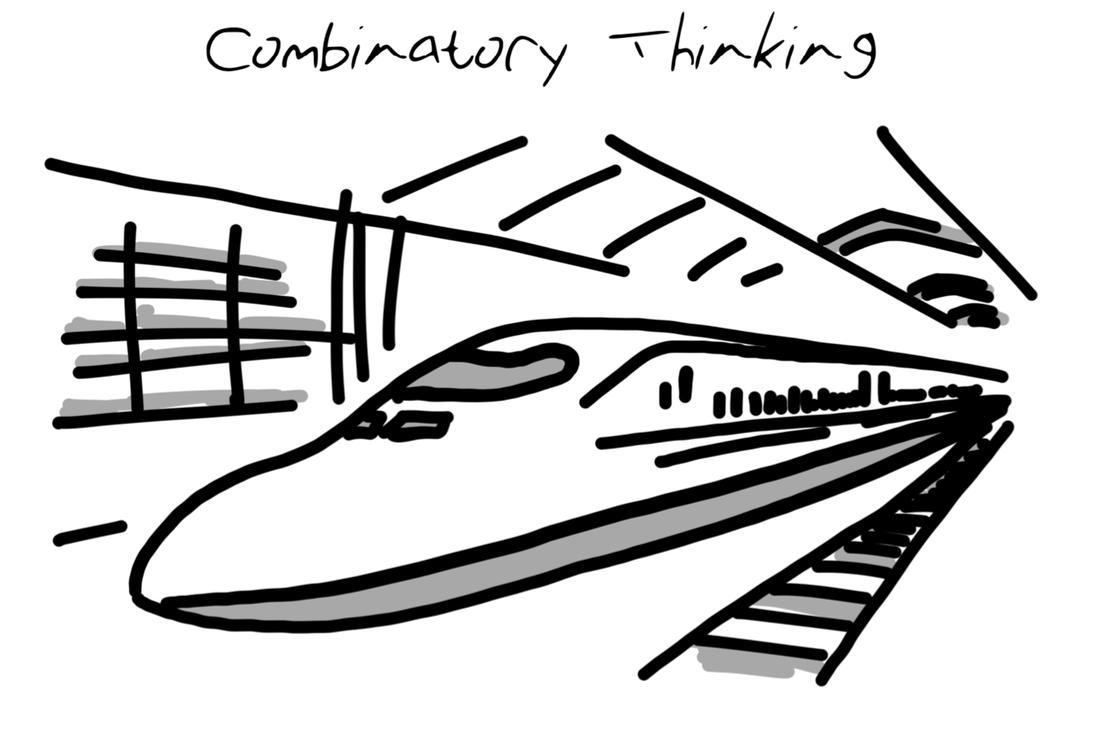

First, as has been mentioned, feedback is optimized when it arrives in the right dose, at the right time. We have all had moments where we were simply not ready to hear what was good for us and so swatted away crucial lessons. On the other end, especially if we have raised or taught children (or been married!), we have all delivered feedback at the wrong time, sending our recipient into a defensive posture, again minimizing the impact of the lesson. Second, and also crucial, is that feedback, done well, helps both the receive and the giver. Not all feedback is good feedback; not all feedback is equally valuable; not all feedback will result in learning (Hattie, 2012). So you can’t just throw it around like fertilizer and expect all the weeds to die and all the plants to, in turn, flourish. In fact, one of the most valuable aspects of good feedback is the effect that it has, to continue the metaphor, not on the weeds and the plants but on the thrower of the fertilizer -- you. Taken together, these pillars of effective feedback – dosage, timing, and reciprocity – help us to notice the value of an immediacy at play in businesses that rely on multi-sided marketplaces, bringing to a fine focus much of what we have been discussing in this book: leading, selling, training, and servicing. When working on their Shinkansen bullet train, trains that travel up to 300 kph, Japanese engineers could not figure out how to reduce the sound boom as trains entered and exited tunnels. They turned to biomimicry, or the combination of nature and engineering, to find a solution. Noting that the beaks of kingfishers allowed them to dive into water without making much of a sound, the Shinkansen engineers reshaped their trains accordingly. Once the fronts of the trains resembled the beaks of the kingfishers, the engineers reached their goal, reducing the sound (Moskvitch, 2017; JNCC, 2018).

Last May, Steve was sitting in his office and writing the agenda for a meeting. He was trying to design a leadership activity for a group that needed to be rejuvenated at a critical time of the year. Concentrating intensely, he did not notice the colleague hiding in his door frame until he heard someone else nearby gently chide the colleague: “Stop pacing in Steve’s doorway and just walk in.”

On his way in, falling into the chair in front of Steve’s desk, and nearly sitting right on his own bike-messenger style bag, the teacher started apologizing profusely for missing a meeting with Steve. Steve was confused. He glanced at his calendar. Looked back at his colleague. Glanced again at his calendar. Then he smiled. “Do you mean next week’s meeting? If you have figured out how to miss next week’s meeting in advance of next week’s meeting, then I’d love to borrow your time machine.” Steve’s colleague was first confused and then relieved. “Thank goodness. Sorry about this,” he said. “Sorry to have wasted your time.” Steve thought back through his interactions with this colleague and realized that this wasn’t the first time that he had confused his appointments with him or with others. And, since he had him in his office, he decided to dig in a little bit. Perhaps he could help him. After a few questions, Steve figured out that this young man’s calendar systems were as good as they needed to be. If anything, they were overly thorough, bordering on obsessive, since they involved an electronic calendar, a smartphone, and an even smarter watch. He was also motivated to do well and to be present at meetings to which he was called. So Steve decided to end the conversation by turning the tables on himself, more by habit than because he thought that it would yield an insight. Steve asked, “How can I help? When I call a meeting with you, is there something that I can do differently to ensure that we both get what we need?" Steve was surprised at how quickly his young colleague was able to answer him. “You can not email me too early.” “In the day?” Steve asked. “No, I am up early. It is not that. It is just that...when you email me four weeks in advance of a meeting, I am less likely to take care of that meeting appointment . . . because it feels less urgent or something. But when you email me a few days in advance, I will never miss the appointment because that is just how I tend to set things up for myself -- around momentum and context. Because, really, almost anything can be moved or shifted, until it cannot be, until it is happening, right?” And with that, he looked at his watch, which had lit up with a reminder that something was happening and was most likely also tapping him on the wrist with some kind of haptic communication feature, then said, “I am going to be late for class, so I have to go. Thanks for chatting.” When he left, Steve tried to get back to the agenda he had been writing, to the design of a leadership exercise, but he kept getting distracted by the non-meeting, non-apology that had just happened in his office. Was this, perhaps, a moment for Steve to think about his own leadership before he thought about the leadership of others? Or was his leadership solid and on course? Put more granularly, should the teacher — in this case, the one lower on the hierarchical chain of command — adjust to Steve, or should Steve — the senior leader with almost two decades of experience — adjust to the teacher? And, plumbing for empathy, what did Steve prefer when he was not actually the one in charge? What did he prefer when he was a producer and not a leader? Steve felt the stirrings of a confused excitement. Confusion because his head was spinning with possibilities and questions; excitement because he knew that this feeling was usually the beginning of insight, of learning. Boredom is not the enemy -- poor teaching is.

Quiet students in classroom might be completely off the teacher’s task. (They might be watching a video or engaging in a chat with a student in another class.) They are bored and disengaged because they cannot connect the task to a personally fulfilling trajectory. Excited students might be responding to a mere trick or joke -- or something that happened outside of class. They are giving off the illusion of being engaged, and not bored, but only because they are temporarily entertained. Disconnected tasks or activities ground learning to a halt. Irrelevant tasks, busywork, or work that could be better handled by a machine encourage students to practice irrelevancy, mindless busyness, and tasks that will be easily replaced by robots. In a graduate school class, one exercise we do is taking the context of a complex situation and simplify it down in such a way that someone not familiar with business (or business-speak) can understand. This paragraph has a lot of information. We don't want them to focus on what the company did or plans to do. Simply put - what is going on? Our students came up with: Boeing may lose more than half of its skilled workforce to retirement by 2020.

The next part of the exercise is to identify the business objective: Boeing now needs to build a talent pipeline of skilled workers. Next, we identify the strategy: By investing in community partnerships and development programs, Boeing can work with learners across the entire life continuum from K-12 students to executives. Finally, we discuss the learning programs that were implemented. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed