|

We are committed to a set of ideas and a process for spreading them. We are trying to capture our evolving understandings and present them. We are trying to reach multiple constituents (in our case, readers) who listen and learn and access information in different ways. Is this not what school leadership is about, too? A constant riffing on a set of core beliefs, rapid prototyping to ensure that we apply what we learn, a continual evolution of program and curriculum — and people — to ensure that our missions play out on modern stages and fields and classrooms, offline and online?

0 Comments

When working on their Shinkansen bullet train, trains that travel up to 300 kph, Japanese engineers could not figure out how to reduce the sound boom as trains entered and exited tunnels. They turned to biomimicry, or the combination of nature and engineering, to find a solution. Noting that the beaks of kingfishers allowed them to dive into water without making much of a sound, the Shinkansen engineers reshaped their trains accordingly. Once the fronts of the trains resembled the beaks of the kingfishers, the engineers reached their goal, reducing the sound (Moskvitch, 2017; JNCC, 2018).

There is a new section on the app that links to posts featuring various 'experts' sharing best practices and project files for download. You can find most of those posts here too.

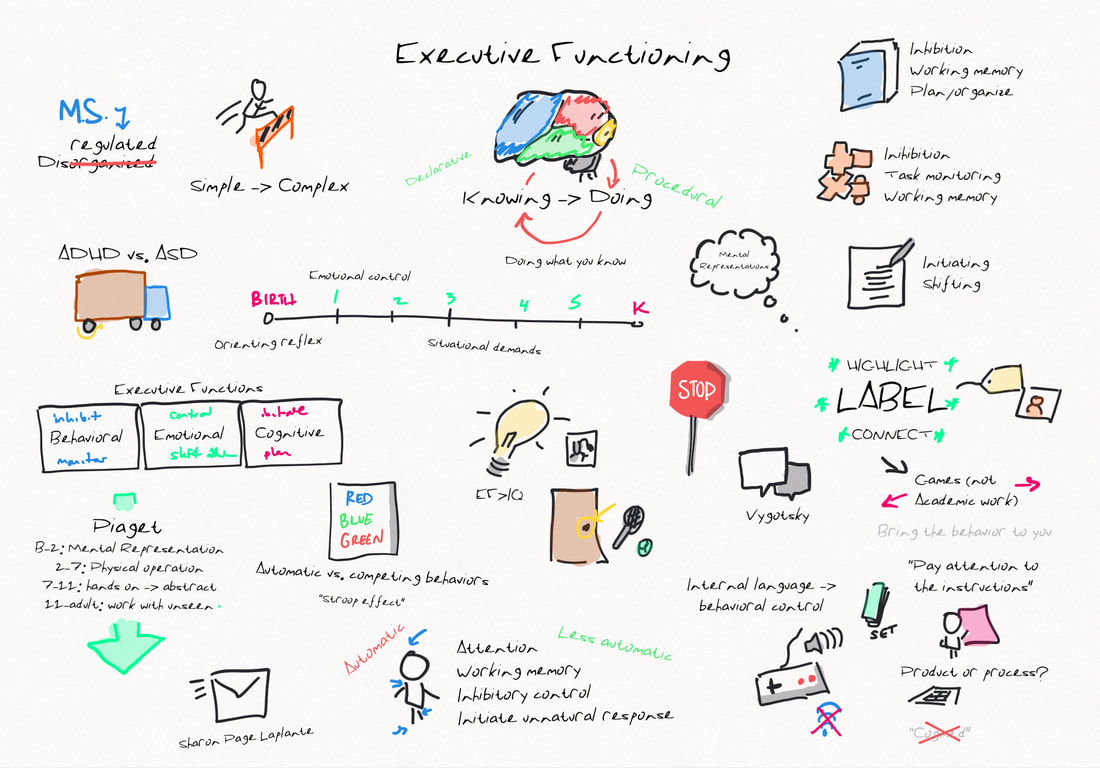

I attended a terrific workshop on emerging approaches to connecting executive functions to educational goals with young children. My notes are above.

If you examine, again, the blended leader, the one who capitalizes on affordances made by control of “time, path, place, and/or pace,” you will see a leader perfectly situated to thrive in a world where the spoils go to the questioners. Blended leaders are the opposite of the leaders who, in only having a hammer, treat every problem like a nail (surely, we have all been on the receiving end of such leaders’ problem-solving approach). Blended leaders, on the contrary, keep lots of tools — whether online or offline — in their toolkits because they are never quite sure which one they will need. What is more, they leave room in their toolkits in case they have to learn how to use a brand new tool when faced with a problem they have not seen — or solved well — before.

Last May, Steve was sitting in his office and writing the agenda for a meeting. He was trying to design a leadership activity for a group that needed to be rejuvenated at a critical time of the year. Concentrating intensely, he did not notice the colleague hiding in his door frame until he heard someone else nearby gently chide the colleague: “Stop pacing in Steve’s doorway and just walk in.”

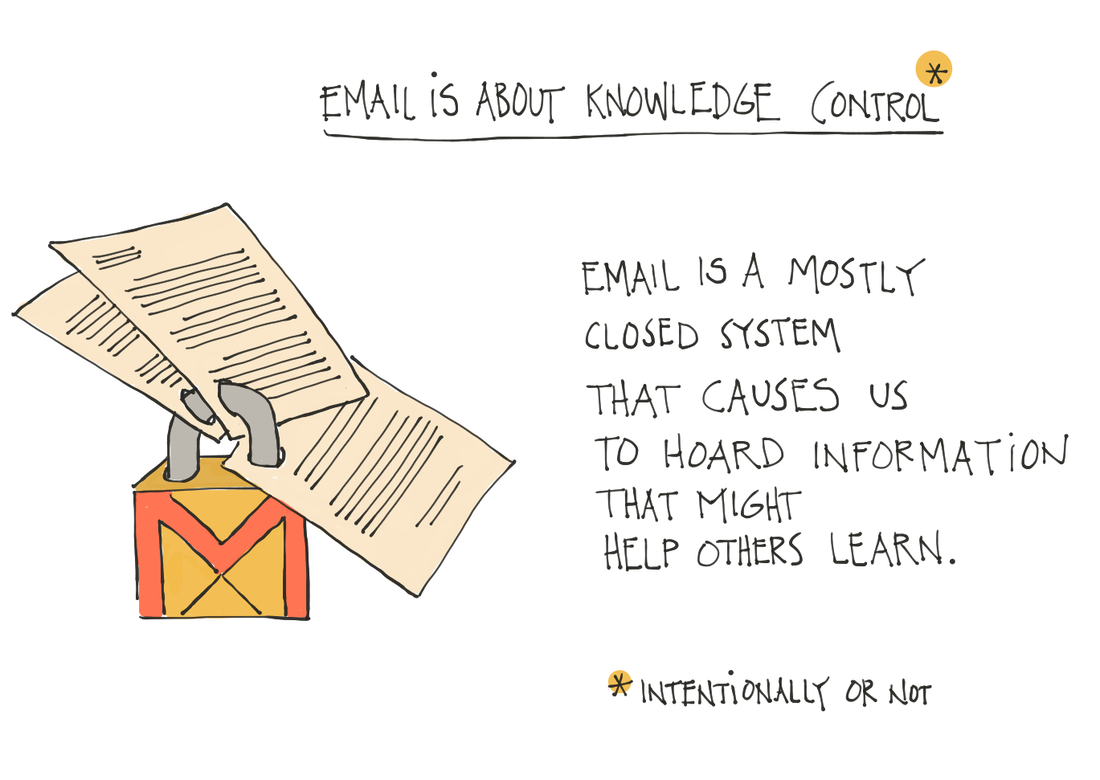

On his way in, falling into the chair in front of Steve’s desk, and nearly sitting right on his own bike-messenger style bag, the teacher started apologizing profusely for missing a meeting with Steve. Steve was confused. He glanced at his calendar. Looked back at his colleague. Glanced again at his calendar. Then he smiled. “Do you mean next week’s meeting? If you have figured out how to miss next week’s meeting in advance of next week’s meeting, then I’d love to borrow your time machine.” Steve’s colleague was first confused and then relieved. “Thank goodness. Sorry about this,” he said. “Sorry to have wasted your time.” Steve thought back through his interactions with this colleague and realized that this wasn’t the first time that he had confused his appointments with him or with others. And, since he had him in his office, he decided to dig in a little bit. Perhaps he could help him. After a few questions, Steve figured out that this young man’s calendar systems were as good as they needed to be. If anything, they were overly thorough, bordering on obsessive, since they involved an electronic calendar, a smartphone, and an even smarter watch. He was also motivated to do well and to be present at meetings to which he was called. So Steve decided to end the conversation by turning the tables on himself, more by habit than because he thought that it would yield an insight. Steve asked, “How can I help? When I call a meeting with you, is there something that I can do differently to ensure that we both get what we need?" Steve was surprised at how quickly his young colleague was able to answer him. “You can not email me too early.” “In the day?” Steve asked. “No, I am up early. It is not that. It is just that...when you email me four weeks in advance of a meeting, I am less likely to take care of that meeting appointment . . . because it feels less urgent or something. But when you email me a few days in advance, I will never miss the appointment because that is just how I tend to set things up for myself -- around momentum and context. Because, really, almost anything can be moved or shifted, until it cannot be, until it is happening, right?” And with that, he looked at his watch, which had lit up with a reminder that something was happening and was most likely also tapping him on the wrist with some kind of haptic communication feature, then said, “I am going to be late for class, so I have to go. Thanks for chatting.” When he left, Steve tried to get back to the agenda he had been writing, to the design of a leadership exercise, but he kept getting distracted by the non-meeting, non-apology that had just happened in his office. Was this, perhaps, a moment for Steve to think about his own leadership before he thought about the leadership of others? Or was his leadership solid and on course? Put more granularly, should the teacher — in this case, the one lower on the hierarchical chain of command — adjust to Steve, or should Steve — the senior leader with almost two decades of experience — adjust to the teacher? And, plumbing for empathy, what did Steve prefer when he was not actually the one in charge? What did he prefer when he was a producer and not a leader? Steve felt the stirrings of a confused excitement. Confusion because his head was spinning with possibilities and questions; excitement because he knew that this feeling was usually the beginning of insight, of learning. Here is a terrific example of some young people explaining their understanding of the water cycle.

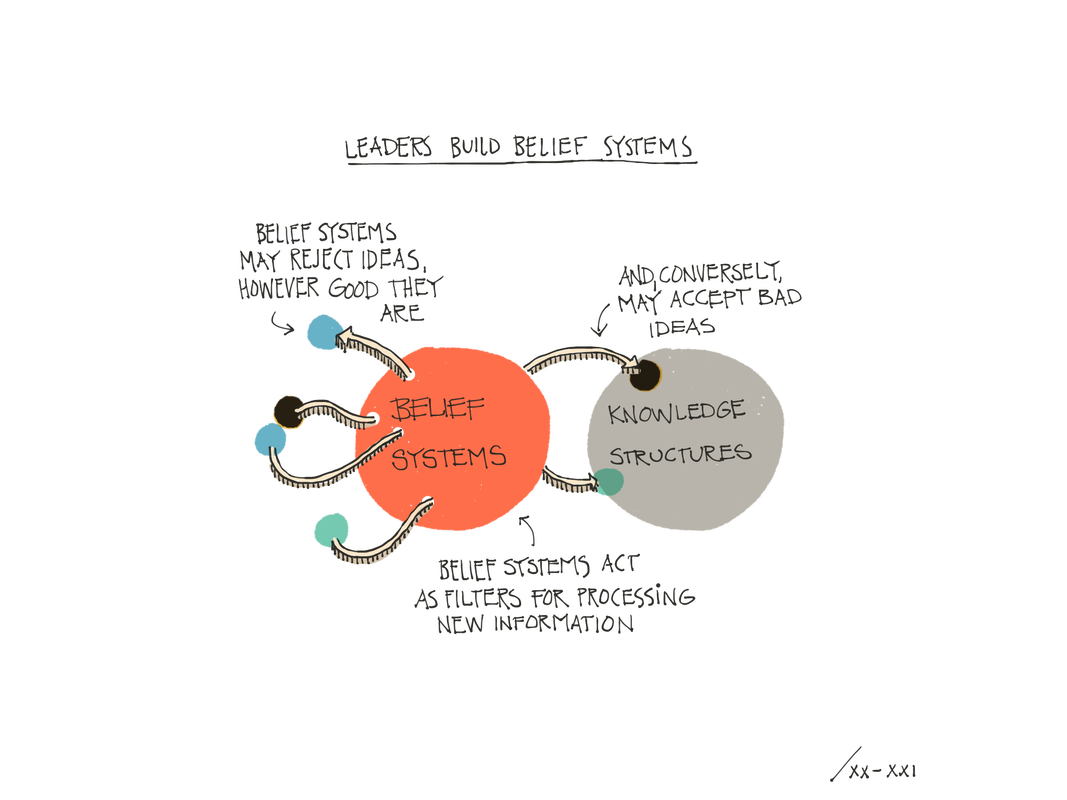

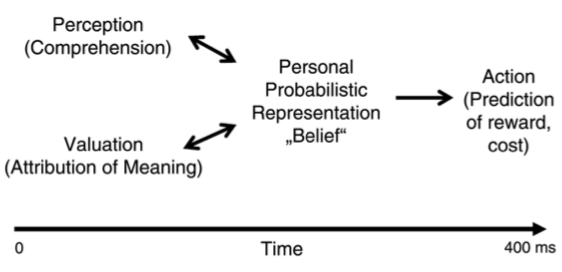

While looking into studies on the intersection of experiences, exposure, and beliefs I stumbled upon this interesting article that looks at the neurology of beliefs. Here is a wordy quote that, when broken down, gives an interesting perspective on this intersection:

"Perceived information is what motivates the generating of actions (Figure 1). Note that believing is inherent in this transforma- tion such that knowledge acquired in the past and represented in probabilistic representations is linked to the future by proba- bilistic predictions. Generating actions involves intentions to act, action selection, inhibition of unwanted acts, and predicting reward and costs of acts (Nachev et al., 2008; Passingham et al., 2010). In general terms, this refers to deciding what to do next. The neuroscientific basis for decision making has been shown to be related to reward valuation (Grabenhorst & Rolls, 2011) and unconscious or intuitive selection that evolves within far less than 400 ms (Chen et al., 2010; Kahnt et al., 2010; Schultze-Kraft et al., 2016). The processes that regulate the performance of actions are replete with probabilistic reward and cost predictions determined by the personal meanings attributed to the mental representations of the signals from the outside world (Friston et al., 2014). The action-perception-valuation triad has been postulated to account, in context of a hierarchical dimension, for computations of physical, social, and cultural matters (Sugiura et al., 2015)." |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed